OCEANIAN

Traditional Oceanian Religion

Oceania is a continent whose religious traditions have been modified and are still changing. While traditional religions were largely supplanted during Western colonization, they survive in many remote areas.

Three major common features mark the original religious traditions of Oceania :.

– the cult of ancestors is a universal feature and seems to have been the basis of all the spiritualities in the different territories (mainland and islanders).

-the concept of mana i.e. the accumulation of power of a sacred order which also causes an accumulation of goods is also shared by all, with the exception of Australia, which stands out more clearly on this point. To mana, we oppose the noa (layman).

-the notion of tapu (or taboo) in other words of sacred prohibition is a last point common to the whole Oceanian world.

In the plastic expression of the sacred, red is the color of the divine, white is the color of the ancestors.

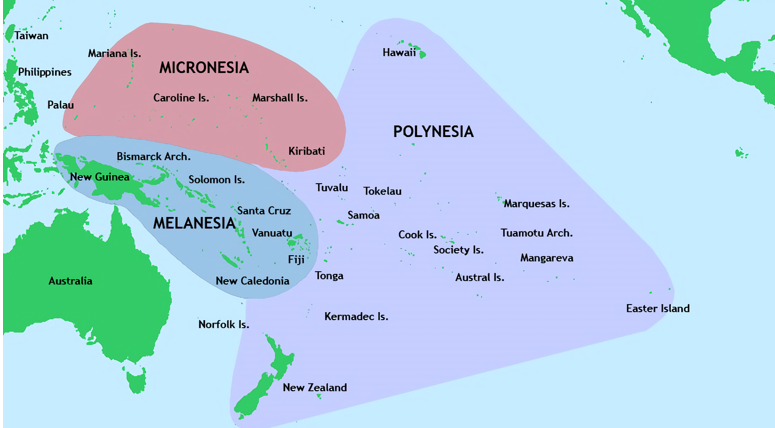

There are four main spiritual areas :

Polynesia over which reigns a common pantheon of gods and heroes. In some of its worship spaces called marae

dance was held

Melanesia which is characterized by a spiritual world composed of invisible entities of which the ancestors are a small

part.

Micronesia where the expression of the sacred is above all based on ancestor worship.

Australia whose spirituality is clearly separated from the rest of Oceania.

Learn More fom Britannica

Polynesian Dances

Remnants or elements of precontact Polynesian music have survived almost everywhere,

either alongside of or within acculturated styles—because of a marked traditionalism, as in Hawaii and New Zealand, or because of a delayed acculturation process, as in many of the smaller and remoter islands. Music serves as a vehicle for Polynesian poetry, as dance is its illustration. The central role of the word explains why Polynesian music is primarily vocal.

Here are three examples :

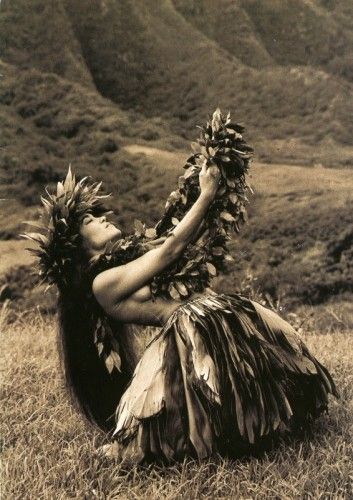

Hula

is the dance of the Native Hawaiians. It is performed by graceful Hula Auana, or powerful Hula Kahiko. Legend says that the Hula was originally performed for Pele, the goddess of fire, by her sister, Hi`iaka. Many Hula chants are an oral record of the history of Hawaii. After the arrival of missionaries on the Hawaiian Islands in 1820, hula was banned. Although the dance was somewhat revived years later for the purpose of religious freedom, King David Kalakaua is credited for the full revival of the hula during his reign between 1874-1891. The art of Hula is credited for preserving the culture of the Native Hawaiians.

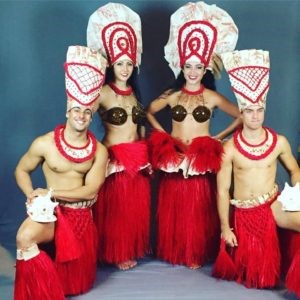

Ori Tahiti

is the dance of the Tahitian people. Otea, consists of gyrating hip movements to drumming Aparima, tells a story through song. Tahitian people are known to love song and dance. In ancient times, the native people of Tahiti would perform various dances for special occasions. There was a dance to greet visitors at a ceremony, dances for prayer and worship, and other dances dedicated to ancient gods. Similar to the history of Hawaii, upon arrival of the missionaries, they banned all songs, games, and dances- as they viewed them as vulgar. Ori Tahiti wasn’t revived until the 1950’s; over a hundred years after it was suppressed

Haka

Haka

is one of New Zeland’s traditional dances. There are many forms of the Haka. One of the most popular is the “Ka Mate.” The Haka portrays strong, war like gestures. Historically, the Haka was performed for a variety of purposes ranging from preparing for battle to funeral services. Another dance of the Maori people is called Poi. Poi balls are weighted balls connected to string. They can be long or short. Poi tells a story while the dancer creates rhythmic and geometric patterns with the poi balls.

Melanesian Dances

There are basically two kinds of dance in Melanesian ceremonies: dances of impersonation and dances of participation. In the first type, the dancer impersonates mythical or ancestral beings; the dancer-actor becomes someone else, and his attire is usually distinctly unhuman or supernatural—consisting often of huge masks and a full otherworldly costume. The dance movements are dictated by the two considerations that the impersonated beings are not human and that the dancer’s attire makes movement difficult. Thus, the dancer’s

movements are restricted to legs and swaying bodies

The second type of dance, that of participation, is often an extension of these dramatic ceremonies, as individuals who do not impersonate spirits often join in and dance with them, imitating the steps of the supernatural. In dances celebrating head-hunting, warfare, funeral rites, or fertility—in which the entire community sometimes participates—the same movements are used, often to the accompaniment of drumming and communal singing. See an example below

Read : Symbols of life and Death in Melanesia by Alphonse Aime

Vanuatu Rom Dance

Vanuatu Rom Dance

The rhythmic beating of tam tams and shakers set the scene as warriors dressed to represent evil spirits emerge, adorned in a thick and somewhat intimidating cloak of dried banana leaves and a conical, brightly painted banana-fibre mask. As the dance begins, story, myth, heritage, and belief entwine with the supernatural in an unfolding rich in symbolism.

Rom dance chants tell stories that reveal the diverse regional and cultural differences across the island of Ambrym. As an ancient ritual imbued with secret knowledge, elders keep the Rom dance and other tribal customs cloaked in mystery. Costumes must be kept in strict hiding until the ceremony begins and if anyone is caught stealing a peek, they must pay the fine of one pig and endure a whipping with a stinging plant! The masks are a symbol of power and are central to a variety of ceremonies, including initiations and circumcisions. Every element of movement, chant and adornment is symbolic. High ranking chiefs and warriors who dance alongside the Rom dancers often wear red flowers in their hair to symbolise pride, majesty, knowledge and strength, as well as a boar tooth necklace to indicate power and wealth. Some chiefs will wear a namale leaf on their back to convey peace, while others wear white bird feathers to suggest both peace and safety.

Participation in these dances, which are also known as ‘kastom’, are dictated by tribal affiliation.

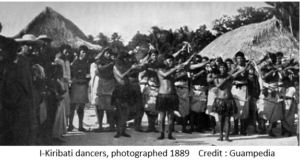

Micronesian dances

Dance movements are mainly of hands and arms in accompaniment to poetry. In some islands, such as Yap (in the western Carolines) and Kiribati, there is a similar concern for rank in the placement of dancers, as well as the emphasis on rehearsed execution of songs and movements. In the Yap empire, for example, dancers from Ulithi, Woleai, and other islands performed and taught their choreography and texts to the Yapese as tribute, even though the dance texts were in languages unintelligible to the Yapese dancers; the function of movements was not to illustrate but to decorate a story .

Concerning the dance as sacred ritual, On some islands the dance tradition has all but disappeared. On Guam a so-called ritual fire dance is performed by Filipino entertainers for visiting tourists at the Guam Hilton hotel. Palau is struggling to revive its dance traditions.

On some islands the dance tradition has all but disappeared. On Guam a so-called ritual fire dance is performed by Filipino entertainers for visiting tourists at the Guam Hilton hotel. Palau is struggling to revive its dance traditions.

But it persists on Kiribati and on Yap.

The extent to which Kiribati dance is considered holdy or sacred is uncertain, although the dancers of old were thought to be inspired by the spirits. by tradition, Kiribati dance was not only a form of entertainment but also as tributes to particular spirits, the unification of two clans (kainga), a form of oral storytelling and simply the display of the skill, beauty and endurance of the dancer

But on Yap the sacred dance still exists. Sometimes the men or women of a village perform the dance for their village, with no outsiders allowed to attend. Yap is now largely Roman Catholic, and the sacred dance is regularly performed as part of the liturgy.

In Yap, the Catholic services are filled with bare-breasted women and men in scanty wraparounds that cover only the genitals!!

Australian and Tasmanian indigenous dances

To this day ceremonies play a very important part in Australian Aboriginal peoples’culture. Ceremonies, or rituals, are still performed in parts of Australia, in order to ensure a plentiful supply of plant and animal foods.

To this day ceremonies play a very important part in Australian Aboriginal peoples’culture. Ceremonies, or rituals, are still performed in parts of Australia, in order to ensure a plentiful supply of plant and animal foods.

They contrast in different territories and regions and are an important part of the education of the young.

Some ceremonies were a rite of passage for young people between 10 and 16 years, representing a point of transition from childhood to adulthood. Most ceremonies combined dance, song, rituals and often elaborate body decoration and costume. The Elders organized and ran ceremonies -like Bora/Burbung -that were designed to teach particular aspects of the lore of their people, spiritual beliefs and survival skills.

Aboriginal people also perform funeral ceremonies They conduct a series of rituals, dances and songs to safeguard the person’s spirit leaves the area and returns to its birth place where it can later be reborn.

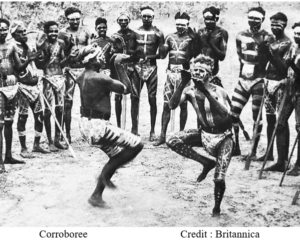

The Corroboree ceremony consists of much singing and dancing, activities by which they convey their history in stories and reenactments of the Dreaming, a mythological period of time that had a beginning but no foreseeable end, during which the natural environment was shaped and humanized by the actions of mythic beings.

Tasmanian Aboriginal communityhas important cultural practices including Singing and dance .They are practiced both for ceremony at exhibitions and festivals. Such practices have strong connections to the past heritage of the Aboriginal people but also celebrate the new styles and emerging talents of contemporary artists.

Top Map : File:Pacific_Culture_Areas.png Credit : Wikipedia