HISTORIC ISSUES

Historic Issues on Dance and Christianity

The history of the relations of dance and Christianity- either as regards the place of dance in cult or as regards the positioning of the church concerning dance- is a passionate challenge for University Research, as many issues in various periods have not been deeply investigated

It s true that practically only the three monotheistic religions have problems with dance ; they seem to constitute an exception inside the vast constellation of spiritualities existing and past

Whereas Judaïsm and Islam excluded plastic arts , Christianity included all arts in its cult with a practically complete exclusion of Dance. Was it always the case through its 2000 years history ? That s the principal challenge of a serious research . An additional subject concerns a deeper examination of the reasons of this attitude

Since the 2d half of the twentieth century some protestant movements , in particular the evangelical ones , claim that dance has its place in the cult – from which it was expelled in the past . Several historic works have been written to justify this thesis . Those works starting from the place of dance in jewish religion, examine the various periods of the 2000 years history considering that although dance was part of the cult in the first three centuries , it started to pose problems after the officialization of the Christian Religion and after centuries of contradictory attitudes which progressively reduced its role , it was completely expelled from the catholic and protestant cult after the Reform. The phenomenon of revivals in the 19th Century contributed to the recognition that dance was not incompatible with christian cult and to its progressive (re?) introduction principally in the evangelical cult .

Dr Lucinda Coleman is a dance educator and choreographer, based in Perth, Australia. Her article,” Worship God in Dance” adapted from her post-graduate research on ‘Dance in the Church’, briefly traces the history of dance in worship from the Judeo-Christian tradition to the Reformation and the Renewal in the church in recent decades . It constitutes an excellent introduction to our subject and it also contains an interesting bibliography .

However it is harder to find in deep researches on specific issues over the last twenty centuries . A synthesis of those researches might be precious to create a more solid history

CID is encouraging researchers either to furnish bibliography or do some research themselves

An online seminar on this subject is to be held in future

Consequently the structure of this page is provisory. Some of the following paragraphs suggest subjects to deepen ; references to known researches are given and – exceptionally – a bibliography specific on this subject is furnished in the end

This page needs – above all – the contribution of everybody

Circular Dance in Early Christianity

Melody Gabrielle Beard-Shouse(Bibliography) suggests that the circular dance in the Acts of John describes an ancient Christian Ritual in a period that gnostic andorthodox viewpoints coexisted. Furthermore, she points outthat this ritual draws heavily on Greek philosophical understandings of circle dances representing order and disorder concluding that this ritual was ecstatic in character, and that it was individually transformative.She also makes a comparative study with the dialogues between Master and Disciples as they are describedin therecently found (fragmentary) apocryphal Gospel of the Saviour(which original is believedto be of the 2d Century) to confirm the idea of the existingcircular dance ritual in the “early Christian plurality”

Dance In The Ethiopian Church

Dance In The Ethiopian Church

Zema, is a form of Christian liturgical chant practiced by the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church. The related musical notation is known as melekket. The tradition began after the sixth century and is traditionally identified with Saint Yared. Through history, the Ethiopian liturgical chants have undergone an evolution similar to that of European liturgical chants.

Zema means a pleasing sound, a song or a melody in Ge’ez, the liturgical language

Students of Ethiopian liturgical chants study the Ge’ez language, and begin practicing singing in childhood. Education takes place in liturgical dance schools called aqwaqwam bét and includes, in addition to singing and dancing, training in traditional instruments such as the käbäro, drums, tsänatsel, sistrum, and mäqwamya. Singing students (däqä mermur) become singers (däbtära) and some will eventually become masters (märigéta). A student is considered ready when he has mastered the complicated genre of qené. It has been suggested by Monneret de Villard that liturgical dance, that always accompanies the music, has its origins in the Ancient Egyptian dance.

Medieval Paraliturgical Dances

On special occasions such as Saints’ days, Christmas and Easter, the clergy performed sacred dances for the congregation who were spectators of these ritual acts.

-Several liturgists mention in their writings the practices of the dance and the game of balloon in the large churches in France like Auxerre during important religious celebrations (15th Century).

Even as late as the 16th century a manuscript describes an Easter carol or ring dance which took place on Easter eve at the church in Sens.

– One of the possible functions of the labyrinth, especially those found in the cathedrals of Reims and Auxerre, was to mark out the area which would be used in an Easter ritual where local monks and clergymen jumped, danced, and tossed a leather ball, called a pelota, to each other.

Medieval Dances performed outside of churches

Dance was found in sacred settings as a part of the many church feasts, and there is an entire repertory of sacred dance songs that celebrate these events

Some of the dances were part of a tradition developed with the approval and guidance of the church and are known as popular sacred dances They were performed in the church, churchyard, or surrounding countryside during religious festivals, saints’ days, weddings or funerals.

Pilgrimages were also the occasion of dances . The behavior of pilgrims was a sensitive issue

In 1407 after a complain about pilgrims “…..to have with them men and women that can well sing wanton songs and some other pilgrimages will have with them some bagpipes…..” The Archibishop of Canterbury replied that music was an entirely acceptable remedy for the tedium and toil of the road and a welcome distraction from the pain that a pilgrim might feel if he hit his foot on a stone

In the Montserrat Monastery , The Llibre Vermell contains a Canconiero Musical with ten pieces of songs dedicated to the Virgin so that pilgrims can “sing and dance devoutly” during their vigils.

We could also mention The dancing procession around the relics of Saint Willibrord in Echternac

in Luxembourg, custom that exists until today.

Ecstatic Dances

In the 14th and 15th centuries two widely known ecstatic dances appeared

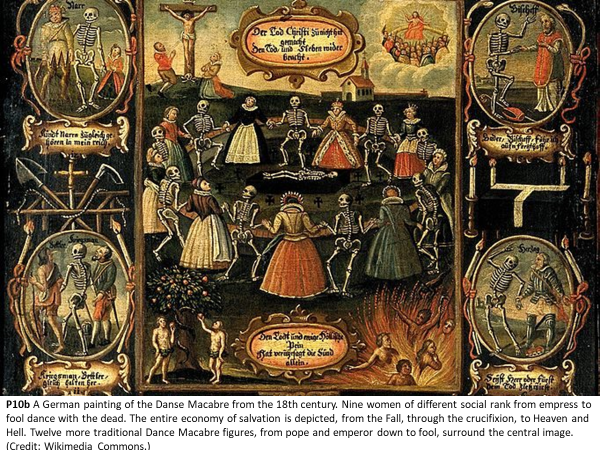

1- Dance macabre , The dancing movement of the characters was a somewhat later development, as at first Death and his victims moved at a slow and dignified gait. But Death, acting the part of a messenger, naturally took the attitude and movement of the day, namely the fiddlers and other musicians, and the dance of death was the result.

2- Dancing mania known as St. Vitus’ dance (a kind of mass hysteria, a wild leaping dance in which the people screamed and foamed with fury, with the appearance of persons possessed.)

Sacred dance in Byzantium

Byzantine dance has its origin from greek Antiquity. The Byzantine Empire was a large pluralistic nation where different types of music and dance could be found in various regions. Furthermore, the society evolved to allow some dancing in Christian sacred places, such as the church. Ex

-moirologia (=laments), which were eventually allowed to be chanted and danced in a circular movement in the narthex (entrance or lobby area, located at the west part of the church

– the Dance of Isaiah, in matrimony which is a thrice encirclement of the vestment table by the bride and groom, in the Byzantine rite of matrimony still existing in our days

– There are also instances recorded of people dancing inside the church, on Easter and Christmas, after Patriarch Theophylactos (10th Century) had granted his permission. Historians do not agree on his precise influence to reconcile pleasure with piety by introducing some lines of pantomime in the services.(till 13th century)

The actual Church of Constantinople considers him as an unworthy Patriarch.

See the video :

Pilgrims in South America

Several catholic pilgrims consist of rich celebrations in which pre-colombian spirituality is evident

Quyllurit’i, Peru

According to the Catholic Church, the festival is in honor of the Lord of Quyllurit’i -or Lord of Star (Brilliant) Snow- originated in the late 18th century after a miracle

The festival attracts thousands of indigenous people who make an annual pilgrimage to the feast, bringing large troupes of dancers and musicians.

The culminating event for the indigenous non-Christian population takes place after the reappearance of Qullqa in the night sky; it is the rising of the sun after the full moon. Tens of thousands of people kneel to greet the first rays of light as the sun rises above the horizon. The pilgrimage and associated festival was inscribed in 2011 on the UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage Lists.

Copacabana, Bolivia

Before 1534, Copacabana was an outpost of Inca occupation , a key to the very ancient shrine and oracle on the Island of Titicaca, a place of worship.

On 2 February 1583, the image of the Virgin Mary was brought to the area. Since then, a series of miracles attributed to the icon made it one of the oldest Marian shrines in the Americas, On 2 February and 6 August, Church festivals are celebrated with indigenous dances.

When the Patriarch meets the little dancer of Degas

“From childhood, we were touched by art, which we considered, with faith in God, as a guide to the depth and truth of things. »

Bartholomew Patriarch of Constantinople Honorary Primate of the Orthodox Church

During his visit to the Goulandris Museum Greece, in front of DEGAS’ “little dancer”

Bibliography

Coleman Lucinda : Worship God in Dance

General Bibliography

Adams D. & Apostolos-Cappadona, D. eds. (1990) Dance as Religious Studies. New York: Crossroad.

Brooke, C. (1971) Medieval Church and Society. London: Sidgwick & Jackson.

Clark, M. & Crisp, C. (1981) The History of Dance. New York: Crown.

Daniels, M. (1981) The Dance in Christianity: A History of Religious Dance through the Ages. New York: Paulist.

Davies, J. G. (1984) Liturgical Dance. London: SCM.

Fallon, D. J. & Wolbers, M. J. eds. (1982) Focus on Dance X: Religion and Dance. Virginia: A.A.H.P.E.R.D.

Gagne, R., Kane, T. & Ver Eecke, R. (1984) Dance in Christian Worship. Washington: Pastoral

Kraus, R. & Chapman, S. (1981) History of the Dance in Art and Education. New Jersey: Prentice-Hall.

Taylor, M. F. (1976) A Time to Dance. Austin: Sharing.

Specific Bibliography

Dickason Catherine (2021) :

Ringleaders of redemption How Medieval Dance became sacred Oxford Studies in Historical Theology

Top Photo : Cuncti Simus Concanentes (Let us all sing) 14th Century Credit : Catherine Ingrassia